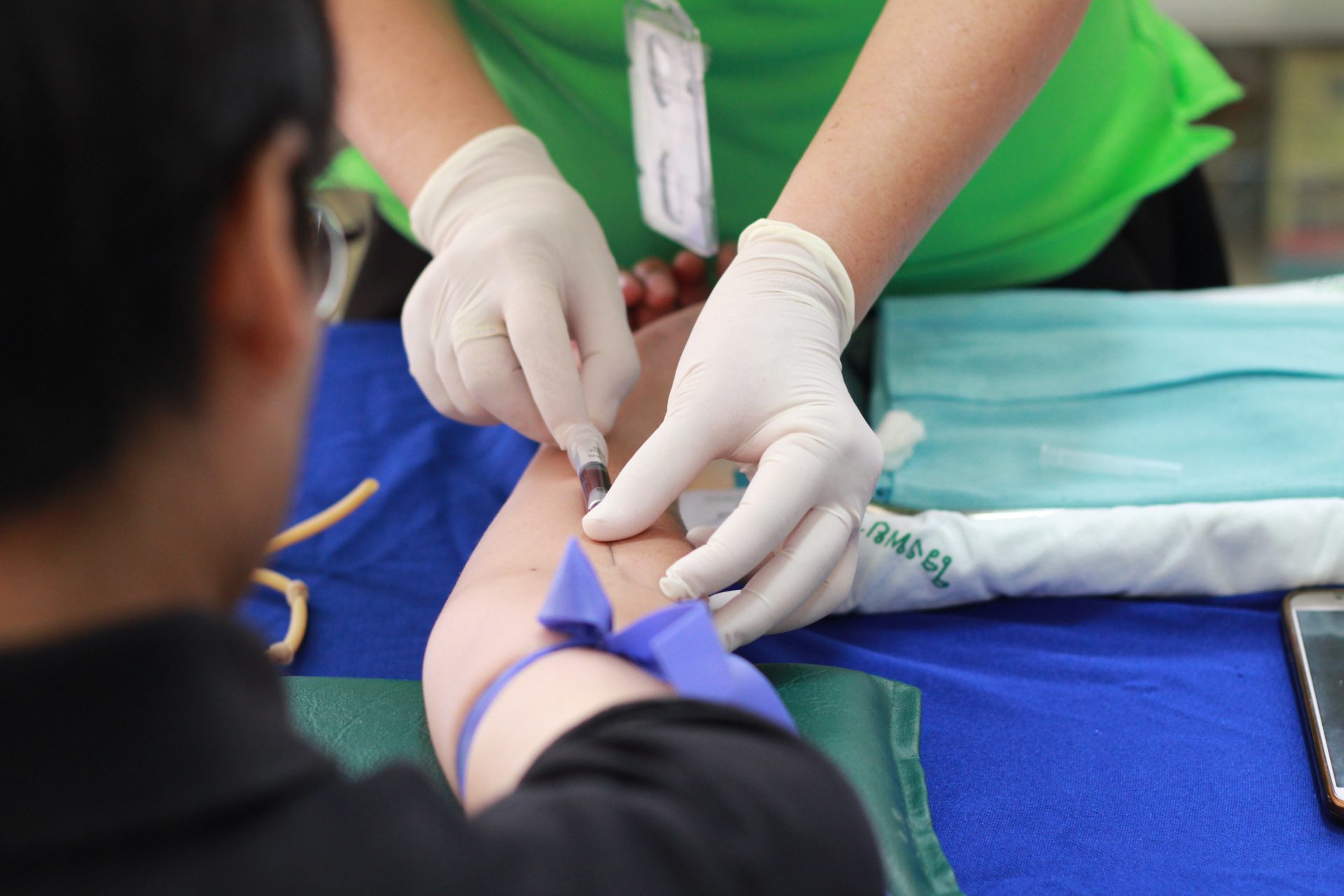

Health testing is under-funded and under-utilised in NZ

Health testing is under-funded and under-utilised in NZ

This is becoming more and more challenging with increasing numbers of blood tests being taken off District Health Board subsidised testing lists. This not only applies to essential nutrients such as vitamin D but also to basic markers of health such as some thyroid function tests.

There are many essential elements that GP’s cannot test for under the funded system but an in-depth discussion of this is beyond the scope of this piece. I have therefore chosen to focus on my top two ‘bug-bears’ as a GP – Vitamin D and free Triiodothyronine (fT3).

The reason I’m particularly passionate about these two is that patients have to be severe enough to have a diagnosed disease before these nutrients are able to be tested for under the funded system. A classic example of the ‘ambulance at the bottom of the cliff’ approach of conventional medicine.

Vitamin D has shown clear evidence of its role in preventing cancer, optimising immune function and easing depression among many other benefits.

However current guidelines that GP’s are advised to follow state:

‘Testing of vitamin D levels is usually only indicated in patients with features of severe deficiency. This includes patients who may have:

- Metabolic bone disease or features such as unexplained fractures or bone pain

- Unexplained raised alkaline phosphatase, low calcium or phosphate levels

- Chronic kidney or liver disease

- Osteoporosis secondary to endocrine disorders, e.g. Cushing syndrome

- Malabsorption of dietary fat, due to conditions such as coeliac disease, previous intestinal surgery or gastric bypass’

The current conventional medicine blanket approach of supplementing only those patients above or those at risk is missing a large number of patients with low or low-normal results. . Vitamin D deficiency is becoming more common. For example, in children up to 17 years old there has been ‘a 15-fold (95% CI, 10-21) increase in [vitamin D deficiency] diagnosis… seen between 2008 and 2014’.

Like Vitamin D, fT3 is only able to be tested in certain circumstances:

- central (secondary)hypothyroidism g., pituitary failure

- TSH is low

- non-compliance with replacement therapy

- early stages of thyroid hormone therapy

- patient is pregnant or postpartum

- patient is on certain medications e.g. amiodarone and lithium

- a rapidly changing thyroid hormone status e.g., after radioactive iodine treatment or thyroiditis https://aoraki.healthpathways.org.nz/index.htm, search ‘Hypothyroidism’

However, whilst fT4 (the storage form of thyroid hormone) is able to be tested in all patients), fT3 is not. FT3 is the active form of thyroid hormone, i.e. the one that acts to drive many of the process in our body including our metabolism. Poor conversion of fT4 to fT4 is a common cause of hypothyroidism symptoms in my clinic.

Reverse T3 (RT3) is also produced from fT4. This hormone attaches to the receptors for fT3 as a control mechanism, for example, by slowing down metabolism. A high RT3 suggests you are converting excess T4 to RT3 and sub-optimal amounts to fT3. This can also lead to a clinically hypothyroid picture, even with normal TSH and fT4 levels. RT3 is unable to be tested at all in New Zealand through the local labs. Integrative GP’s, nutritionists and naturopaths can order them to be done in overseas labs, but these are not funded.

The other issue is that even if testing is done (as is the case with thyroid stimulating hormone or TSH) management is not always implemented in a timely fashion before the patient falls off the proverbial ‘cliff’. This is also another ‘bug-bear’ and the topic for my next opinion piece.